17 September 2025

By Ben Estes

Contributing Writer

(Veritenews.org) — Dark clouds and thunder are rolling up from the south of Whitney Plantation on a sticky late July day.

It won’t be long before the sky opens up and heavy rains soak the former rice, indigo, and sugarcane plantation. It was once home to hundreds of enslaved people and is now one of the few places in the world exclusively devoted to telling the stories of those who worked the land without choice and under constant threat of violence.

Ibrahima Seck and the Whitney Plantation have been teaching people from all over the world about slavery in Louisiana.

Photo by Christiana Botic/Verite News and Catchlight local/Report for America

It’s already like an oven inside one of the small slave cabins on display at Whitney, about an hour’s drive west of New Orleans. When the storm hits, the cabin will be wet inside and out. Rain may come through the roof; it will certainly leak through the gaps between the cypress planks that make up its walls. It will be baking, damp, and suffocating.

The remaining cabins, two of 22 that were once on the plantation, aren’t places anyone would want to call home. Yet people did until 1975.

Before Whitney was Whitney, it was owned by the Haydel family for 110 years, holding about 350 people in bondage over the decades from the 1750s until after the end of the Civil War. The plantation, like almost all industry surrounding New Orleans in the 19th century, was heavily dependent on slave labor and generated great wealth for its white owners.

During its most profitable years, from 1840 to 1860, more than 100 enslaved people worked at the plantation, which produced more than 400,000 pounds of sugar annually. That would translate to almost $1 million in gross profits in today’s dollars.

In 1999, John Cummings bought the plantation from the Formosa Chemicals and Fibre Corporation, which had intended to build the world’s largest rayon manufacturing plant there. Cummings invested millions of dollars and restored the site as a museum focusing on the lives of enslaved people. It opened to the public on Dec. 7, 2014, and has been a nonprofit institution since 2019.

Standing on the same ground where generations of families lived, worked under extreme and dangerous conditions, and died without ever tasting public freedom gives Whitney a sense of the sacred. Surrounded by the “big house, blacksmith shop, giant sugar kettles, and primitive cabins, the passage of time is almost erased.

Dr. Ibrahima Seck, a history professor from Senegal and the plantation’s director of research, is often the last to leave the site when the day is done. During those times, when he is standing alone, listening as the breeze rustles the cane plants, he says he often feels the presence of those who were forced to work here.

Walking along Esplanade Avenue in New Orleans, where thousands of people were sold from the oppressive slave pens, or in the public spectacles at the city’s St. Louis Hotel, now the Omni Royal, a site where slave auctions took place almost daily, can evoke the dreadful reality of the history of slavery in America, but not to the same degree as at Whitney.

****

“I feel myself like I’m on a mission and I was elected to fulfill that mission,” Seck says, while giving a tour of the grounds. He says that even as a child in his home country of Senegal, he knew he would go on a quest to tell the story of slavery.

“Things don’t just happen by chance,” says Seck, a former Fulbright scholar who joined Cummings to work at Whitney full-time in 2013.

When Seck started at Whitney, most area plantation tours focused on the lives of the masters. “And that had to be stopped. Maybe we had two places where slavery was addressed, but not to the extent we went to in telling the story of slavery.”

***

Ambrose Heidel came to Louisiana with his mother and siblings from Germany in 1721. He purchased the property that would become Haydel Plantation in 1752 and established a small indigo plantation. The indigo plant produced chemicals that could be used to create a vivid blue dye highly prized in European fashion before other methods were developed.

Ambroise’s son, Jean Jacques Haydel, took over the plantation in the late 18th century and transitioned from indigo to sugar production in about 1800.

After the Civil War, the plantation was sold, and the new owner named it after his grandson, Harry Whitney. The plantation operated under various owners until 1975.

The land “eventually became one of the most important sugar plantations in Louisiana,” according to Seck’s book “Bouki Fait Gombo: A History of the Slave Community of Habitation Haydel (Whitney Plantation) Louisiana, 1750-1860.”

That area along the west bank of the Mississippi River in St. Charles, St. John the Baptist, and St. James parishes was known as the German Coast because of the influx of German settlers. The slave-powered agricultural interests there would play a significant role in making New Orleans a center of American commerce.

“Under French rule (1699-1763), the German Coast soon became the main supplier of food to New Orleans through the hard work of settlers aided by their white indentured servants and African slaves. … Wealth and comfort came later with the massive importation of slaves and the development of the indigo production under Spanish rule (1763-1803),” according to Seck’s book.

“The collapse of the indigo industry at the end of the eighteenth century was soon followed by the birth of the sugar industry … production skyrocketed with the Louisiana Purchase (1803) and a large influx of slaves, including thousands smuggled from Africa and the Caribbean islands.”

Enslaved Africans at Haydel had many jobs: clearing the land, planting crops, processing indigo and later working the sugar mills, building levees, carpentry work, caring for horses, cows, poultry, and other plantation animals. The list goes on and on.

All that work transformed the plantation from “a small farm entirely dedicated to food crops [with livestock consisting of a single pig in 1724] … into a huge agro-industrial unit,” according to Seck’s book.

Seck wrote that the family ultimately achieved a “high level of economic success and cultural sophistication …

“However, it should never be forgotten that the process of perpetual economic growth, which led to luxury, was made possible by the hard work of hundreds of African slaves and their descendants.”

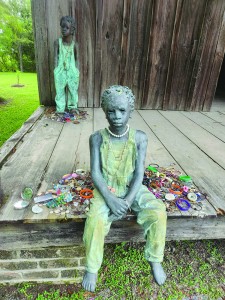

Sculptures outside a former slave cabin at Whitney Plantation.

Photo by Ben Estes/Verite News

***

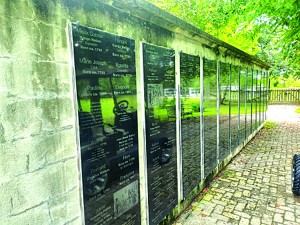

Honoring those who were enslaved is one of Whitney’s top priorities. There are three main memorial sites: the Wall of Honor, the German Coast Uprising memorial, and the Field of Angels.

The Wall of Honor is dedicated to all who were enslaved at the plantation, and includes a list of those who lived and worked there based on sales records and other documents. It also includes first-person narratives documented by the WPA Federal Writers’ Project in the mid-1930s. In addition, there is an 18-wall memorial dedicated to the 107,000 people enslaved in Louisiana between 1719 and 1820 as documented by historian Gwendolyn Midlo Hall.

Then there is the Field of Angels, a memorial dedicated to children who died in slavery, most of them before their second or third birthday, Seck says.

“And we have 2,200 names. We found them in the archive of the Catholic Church. The Catholic church used to record the baptism and the death of enslaved people. So when we dive into those archives also, it was just really shocking to see so many children who died, many of them stillborn. … Some of them were born in the fields.”

Finally, there is the German Coast Uprising memorial. The 1811 rebellion was the largest slave revolt in U.S. history, involving hundreds of enslaved people who marched along River Road from St John the Baptist Parish toward New Orleans. Their goal, Seck says, was “to storm the city of New Orleans and maybe start a free nation like Haiti,” which became the first free Black republic in the world in 1804.

Ultimately, they were overwhelmed by parish militias and federal troops. Those who weren’t killed outright were later executed. “Dozens of them were condemned to death and then decapitated with their heads placed on poles in front of the plantation where they belonged,” Seck says.

“They were decapitated in front of men, women and children. What I call the pedagogy of terrorism. Barbarism. In order to tell the people who were enslaved, if you try to do this again, that would happen to you.”

The memorial consists of 63 sculpted ceramic heads mounted on steel rods. Visitors leave trinkets there – sunglasses, bracelets, coins, and other items – to honor the dead.

“But this never stopped them from resisting until the Civil War came, when they had many people who were maroons (runaways) running into the swamp, who joined the U.S. army,” Seck says. “And Louisiana ended by contributing 25,000 troops to the Union army. … And those are the memorials we built for our interpretation of slavery.”

***

The 1811 uprising was the most feared form of rebellion by enslaved plantation workers against their treatment, but it certainly wasn’t the only one.

Sugar production was difficult and dangerous work involving sharp machetes used for harvesting, boiling kettles to cook down the sugar, open furnaces, and grinding rollers. Workers put in 18-hour days; death and injury were common.

“It is estimated that when sugarcane became the cash crop of Louisiana, the state lost, every decade, 13 percent of its enslaved population,” Seck says.

Unwilling to accept these terrible conditions, many ran away and established communities in the swamps of southeastern Louisiana. They sometimes traded with poor white people in the area and lived in at least a form of quasi-freedom.

Others participated in more passive forms of resistance, singing songs and sharing stories from their homelands. Br’er Rabbit, a trickster figure, has African roots. He became a famous character in the Uncle Remus stories and may have served as the inspiration for the Warner Bros.’ Bugs Bunny cartoon character. Several genres of American music are rooted in the culture of enslaved people, including gospel and blues music as well as jazz and rock ‘n’ roll.

“And you see, there’s so many things to learn about slavery,” says Seck, who is particularly interested in America’s musical connections to Africa.

“People need to be educated to that extent to see a full picture of slavery and let them know that there are many things they are enjoying today in this country. Those things started on the plantations because Africans came over here with their humanity.

“They brought over here their humanity and also the culture, their civilizations, you see? And there is no shame to address the history of slavery. These are things of the past. We have to address them. Because this country is suffering. This country is. You know, you have many people over here who are still suffering from the legacies of slavery.”

***

Ashley Rogers, executive director at Whitney, believes that it is fundamental for Americans to understand the country’s involvement in the institution of slavery.

“Our mission is to educate the public about the history and legacies of slavery in the United States. So very simple. But, yeah, so that’s our whole brief. And we talk not just about, you know, the history of slavery on this plantation, but also slavery more broadly throughout the South, and also what came after slavery, because this plantation operated until 1975.”

Visitation was good after the plantation opened to the public in December 2014. But it went down by 85 percent during the COVID-19 pandemic, and Hurricane Ida caused more than $1 million in damage in August 2021. However, things are on the rebound, Rogers says in an interview.

“It was a really hard few years, and so we’ve been sort of slowly bouncing back,” she says, adding that annual visitation is now around 80,000 to 85,000, still 20,000 to 30,000 shy of the pre-COVID numbers.

Visitation numbers show a good percentage of younger visitors (most museums skew toward older demographics), but there are not as many visiting school groups, perhaps a reflection of today’s political climate, Rogers says.

“Suddenly everybody’s concerned about the curriculum in school being, like, too ‘woke’ or whatever. … A lot of the teachers who came reported that they have difficulty talking to their students about slavery. And that’s even outside of, like, the restrictions of critical race theory.”

Asked if she considers Whitney to be the closest thing to a museum solely devoted to the institution of slavery, Rogers wavers.

“This is what people have said about us — that we’re like the first slavery museum. … I’m always cautious about that because I have so many friends in the museum field and especially like Black museum practitioners who have been doing this work on their own and working very hard for decades, that I don’t want Whitney to, like, take up space in that.”

****

One notable example would be the work Kathe Hambrick began in 199, which led to her founding of the River Road African American Museum in 1994. But whether Whitney can claim some unique status as a slavery museum is beside the point.

What is important is whether Americans have access to their history — especially when it comes to this vital topic.

The fact is that despite documented evidence that 135,000 people were sold in New Orleans before slavery was abolished, the city has nothing like The National World War II Museum when it comes to slavery.

“It’s wonderful. I love to visit there,” Rogers says of the WWII museum.

“But what do you get when you’re looking for the history of slavery in New Orleans? You know, you can go on Esplanade, and you can see where the slave pens were. And you can see where Solomon Northup was jailed. And you can go around town and find a few historical markers and learn some things, but it’s just not enough, as far as I’m concerned.

“If you’re walking around the French Quarter today, you can be blissfully unaware of the fact that slavery built that city, but if you had visited the city in 1850, you would not have been able to ignore slavery.”

Ideally, New Orleans would have slavery memorials similar to Berlin’s Stolpersteine or Stumbling Stones, thousands of in-ground markers placed around Europe that note locations where Nazi victims lived. Rogers is skeptical that something like that could happen because the tourism culture of New Orleans is designed to make people feel good, not to face the horrific history of American slavery.

“It’s like keeping them fed, keeping them happy, keeping them drunk, getting them walking around the corner. And you know … we shouldn’t be telling them about the fact that their hotel used to be one of the major auction sites in the United States, because that will bum everyone out.”

Rogers says America has yet to acknowledge the totality of slavery in part because it is just too painful.

“We have no way to publicly grieve or to celebrate the lives of enslaved people. And so if you put up the names of enslaved people, you automatically have a whole group of people saying, ‘Why are we talking about that?’”

One reason why many Americans are reluctant to confront the country’s legacy of slavery is because there is a debt owed, Rogers says.

“We all understand the debt is too high. It can never be repaid. And like somewhere I think that psychological problem is hanging over dealing with slavery because it is about stolen labor for over 200 years.”

Historical facts like America’s acceptance of slavery and the dispossession and slaughter of Indigenous Americans challenge our views about the founding fathers and their ideals of liberty and equality.

Over the past few months, the Trump administration has sought to steer the discussion of American history toward what it describes as a more positive view of painful subjects, pointing out that the country managed to end slavery with the Civil War, opened up the West, and sacrificed thousands of lives to end Nazi tyranny overseas.

On Aug. 12, the White House announced it would conduct a review of Smithsonian Institution exhibits “to assess tone, historical framing and alignment with American ideals.”

This followed a March executive order from Trump titled “Restoring Truth and Sanity to American History.” Trump claimed in the order that the Smithsonian had “come under the influence of a divisive, race-centered ideology” and that it promoted “narratives that portray American and Western values as inherently harmful and oppressive.”

Last spring, two federal grants to Whitney were rescinded, only to be restored a few weeks later. But Rogers says she is not expecting to receive more such grants anytime soon, which at least means the government cannot censor Whitney’s messages.

“I also think that if you love your country, you have to understand it completely,” she says. “I actually think that you could argue about what patriotism means. But I don’t believe in blind patriotism for sure. If I’m gonna love this place, I have to know everything that happened here.”

****

In the meantime, Seck will continue to do more research and work at Whitney to educate the thousands of people who visit each year.

At 65, he has retired from his academic work in Senegal but continues as Whitney’s director of research. He says the study of slavery and what went on at Whitney will never end for him.

He is currently looking at Louisiana bank archives to study how the plantation financed the sugar business.

He plans on being the last to leave here for years to come. Will he ever stop?

“No, no, there is no retirement for this.”

This article originally published in the September 15, 2025 print edition of The Louisiana Weekly newspaper.