17 September 2025

By Christopher Tidmore

Contributing Writer

It was a place where Black families could go and have fun!

To jump the fence into Lincoln Beach, over the seawall at Hayne Boulevard, one can often hear Latin music drifting past and see more Honduran and Mexican families at play than African Americans.

Lincoln Beach came into existence as a refuge from those racially excluded from the holiday-making opportunities elsewhere. Today in that spirit, many undocumented families feel safe bringing their children to its sands. They are able to do so, in large part, thanks to a committed group of mostly African-Americans volunteers, led by Sage Michael and Reggie Ford, who have fought to preserve the legacy of this distinct tree-shaded sandbox on the estuary, regularly picking up the trash and keeping this historically Black beach passable.

Photo by Keith Weldon Medley

Certainly, the New Orleans City government has done the volunteers few favors. Despite promising to allocate $24.6 million and plan for a 2025 reopening of Lincoln Beach, municipal sanitation often does not even try to pick up the bags of trash the volunteers carefully collect. Often, they have to pile it up under one of the former shelters.

“Every time we clear anything out from there it then encourages more people to go,” Department of Public Works’ acting chief of staff Cheryn Robles once observed as the reason for her inaction (though she has personally expressed hopes that the beach would be reopened soon.)

It takes resolve just to get into Lincoln Beach. Lacking even a crosswalk, pedestrians dodge oncoming traffic only to be greeted by a locked gate, and so must ascend a steep pyramidal incline sweeping beside and above. Aside the last barrier atop, helpful previous beachgoers have left milk cartons and shipping containers to form an impromptu ladder, so one can boost oneself over the bent chain-link fence. Miss your aim as you swing your leg over to climb down, though, and you fall onto the gravel-lined railroad tracks – all because the city thinks it is too inconvenient to open the gates below.

The modern Lincoln Beach, what came to be one of most noted Black amusement parks with amenities in the United States, was only constructed because city officials were shamed by a series of African-Americans deaths at a nearby swimming hole. In the first half of the 20th century, Black New Orleanians were barred from entry at Pontchartrain Beach, so they braved the sinkholes at the Seabrook Beach track, often fatally. With drowning deaths mounting because of uneven ground and sinkholes sucking swimmers under, the city sought to outlaw swimming there in 1943.

The following year, The Louisiana Weekly editorialized, “It is a disgrace to the citizens…that out of the many miles of waterfront around [New Orleans], not one foot is available to…the almost 180,000 tax-paying Negro people in our city.”

Black New Orleanians had only one option to legally swim in Lake Pontchartrain, one hard-to-reach swimming locale which had opened with little fanfare in 1938 across the Industrial Canal. However, at the time, the future Lincoln Beach proved even more inaccessible than even today, fourteen miles from the French Quarter and only accessible by twelve miles of unpaved road. United Fruit President Sam Zemurray had donated 2.3 acres of unwanted former waterfront orchards to the city, who then turned the parcel over to the Orleans Parish Levee Board. Lacking any other use, board members designated it a “permanent colored” beach to silence critics, particularly this newspaper.

No matter that less than four miles away, 175 fishing camps dumped so much contaminated raw sewage into the lake that city health officials quickly begged the Levee Board to close the beach. Moreover, if the pollution did not draw blood from potential swimmers, resident alligators and snakes would. Nevertheless, Lincoln Beach, re-dubbed after the 16th president, sat out-of-sight, out-of-mind for local officials, too far away from real estate to affect home prices and unreachable by public transportation. Like today, though, despite the hurdles, families came.

By 1940, the Work Progress Administration had built a sand beach and a bathhouse, as well as filling in a few of the gaping holes. Still lacking lifeguards or any other safety elements present at Pontchartrain Beach, complaints grew so loud that, by 1951, newly elected Mayor Chep Morrison and the Levee Board announced a $500,000 plan to refurbish Lincoln Beach and, as they said “to make it the equal” of its Caucasian competitor. Barges dumped white sand along the expanded shoreline a quarter mile in length and fill was used to expand the site to 17 acres from its original 2.3. Three swimming pools, a wading pool for children, a large swimming pool and a separate deep-water diving pool, were constructed along with a purification plant. Adjacent to the pool sat a new bath house with approximately 2,000 lockers for the use of both lake and pool bathers. Lastly, the area across the highway from the beach was landscaped for use as picnic grounds – and a restaurant and midway were added.

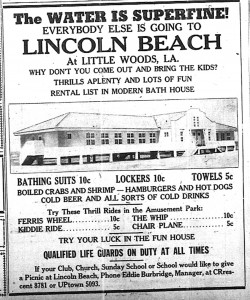

A Lincoln Beach advertisement that appeared in The Louisiana Weekly during its heyday.

Another $500,000 would be spent when the Levee Board leased Lincoln Beach to the white-owned, for-profit Lincoln Beach Corporation to add a rollercoaster, arcade and Ferris wheel as well as numerous other rides. On May 8, 1954, Mayor Morrison, Gov. Robert Kennon and a host of other state and local dignitaries cut the ribbon on a huge dedication ceremony. At 9 a.m., Lincoln Beach manager Walter Wright threw open the gates, selling the first ticket to 11-year-old Paul Castille who led another 10,000 visitors down the midway to the sounds of Papa Celestine’s Dixieland Jazz Band. The marching band from Booker T. Washington High School paraded next amidst the palm trees and rose bushes. In the adjoining 16-foot-deep pool, James “Pump” Chatman conducted coordinated team diving stunts from the 10-meter board. (Lincoln Beach would go on to provide a rare opportunity in the Deep South for Black divers to hone and display their skills.)

More than 25,000 people from Louisiana, Alabama and Mississippi visited within three weeks. This first-rate Black amenity proved such a singular event (in a city that was one-third Black) that The Louisiana Weekly printed the names of every employee, from the onsite nurse to the standby lifeguard.

Every week thereafter, advertisements in the Weekly beckoned residents to “Take a dip day or night” and “Relax in the cool summer breeze on Lake Pontchartrain.” Lincoln Beach ended 1954 with a month-long competition for the title of Miss Lincoln Beach. McDonogh No. 35 High School student June Foster emerged victorious, receiving a 50-inch gold-plated cup, a dozen roses, a music scholarship and gifts from Phil Werlein and the People’s Defense League. Jet magazine published a photo of her receiving a kiss from Nat King Cole, who served as master of ceremonies.

In 1956, a 3,500-car parking lot opened along with new rides. By April 1957, Wright organized a Negro State Fair at Lincoln Beach with themes of music, youth and labor, highlighting his community’s commitment to education and culture. (The popular Wright received nearly 40,000 votes in a 1960 campaign for lieutenant governor of Louisiana.) In the years that followed, Lincoln Beach lured Southern travelers, calling itself the “Coney Island of the South.” National acts with local roots were showcased; customers paid 50 cents a ticket to see Aaron Neville, Fats Domino and many others.

Photos taken at the beach regularly made the Weekly’s front page: beauty queens like Miss Foster, talent-contest winners, divers and children in swim caps. Juxtaposed against these celebratory images were more sobering stories in this newspaper – A.P. Tureaud, chief legal counsel for the New Orleans chapter of the N.A.A.C.P., leading the fight to integrate public parks and the Orleans Parish school system just as the city of San Antonio, Texas, closed a dozen public pools after a Black Sunday School class swam in one.

By 1965, passage of the federal Civil Rights Act banned segregation in public places. Pontchartrain Beach immediately closed its swimming pools. A few days later, a Louisiana Weekly headline proclaimed, “Lincoln Beach Closes Down, Mum on Reason.” The story reported, “While no racial issues were discussed publicly, it is known that the lease agreement carried an escape clause providing that if the segregation or separation of the races become impossible…the lease would be canceled within 30 days.”

The Lincoln Beach Corporation had recently signed a ten-year lease, causing the Levee Board to sue for breach of contract. The Board ultimately lost, and the Ferris wheel was left to rust in the humidity. Pontchartrain Beach became the only option for Black New Orleanians, but hostility from white patrons continued until its closure in 1983.

At the same time, as Caucasians departed for the Jefferson Parish suburbs, New Orleans East became the destination for middle-class Black and Vietnamese families (after the fall of South Vietnam). Multiple proposals were floated to bring back Lincoln Beach. At one point, the Levee Board leased the land to build a marina. When it failed, the city budgeted $300,000 (roughly $1.6 million today) for picnic tables, a fishing pier and a boat launch. Then, developers proposed condos, a waterpark, an amphitheater and a training facility for the New Orleans Saints football team. None were built.

Throughout this period, locals used the beach illicitly, yet Lake Pontchartrain was still polluted with sewage and industrial runoff, and again, the state health department advised against swimming. By 1985, the Levee Board re-designated 23,000 acres of their tract as the Bayou Sauvage National Wildlife Refuge, trading remaining sections of Lincoln Beach to a firm called New Orleans Canal, Inc., in exchange for 50 acres of parkland elsewhere. By 1989, the canal company filed for bankruptcy. No creditors wanted Lincoln Beach, and it was returned to the Levee Board as a tax write-off.

The following year, the Levee Board settled a lawsuit for $4.9 million, after a child fell off a pier and was paralyzed. Eventually, the levee police erected barriers to illegally limit access along the five-and-a-half miles of seawall. This newspaper printed a series of articles over those years about the lack of access to the lakefront by citizens of New Orleans East, ultimately reporting in 1997 that the Levee Board committed $1.5 million to clean up Lincoln Beach, employing an engineering firm to draw up a master plan. It outlined a $20 million project with a restored beach and entertainment plaza, yet no funding avenues to underwrite the work were ever offered.

Later that year, however, a University of New Orleans biologist was able to commence a $2-million marsh-restoration project, underwritten by the Sewerage and Water Board, funded as part of an EPA consent decree. However by 1998, the Levee Board backed out of even that, claiming that New Orleans Canal, Inc. had failed to pay its property taxes, and, as a result, the City of New Orleans – and not the Orleans Levee Board – was actually the owner of Lincoln Beach!

Multiple proposals came over the next decade to restore Lincoln Beach, including an All Congregations Together (ACT) fundraiser featuring Irma Thomas, who once sang for fans at the resort. Working from the Levee Board’s masterplan, the city demolished several structures but balked at redeveloping the remediated site, putting plans on hold by the middle of May 2005. Post-Katrina, squatters took up residence, calling the property “Trash Beach.” Throughout the years of recovery, little changed until Earth Day of 2018. The beach experienced its biggest party since the 1960s with throbbing bass thumping off tree trunks and fire pits in the sand. The organizer, 22-year-old Angelo Levene, estimated that 4,000 people attended the three-day rave, including 120 DJs playing six makeshift stages. While the hundreds of cars parked along Hayne Boulevard did eventually draw police units to the scene, no one was arrested for trespassing. The cops just cautioned the racially-mixed crowd to stay off the railroad tracks, essentially the same warning they would extend any future visitors over the next decade.

In the midst of COVID pandemic May of 2020, Michael “Sage Michael” Pellet and Tricia “Blyss” Wallace launched “Clean Up and Chill,” an effort to beautify the property. Since then, most Sundays, volunteers for the organization New Orleans for Lincoln Beach have filled thousands of contractor bags with litter. Though they have been trespassing, Pellet said the volunteers just could not stand to see the area trashed. “We’re not trying to alienate the city, but we want to hold them accountable,” he later told WWL. Likewise, Reggie Ford, an artist and member of New Orleans for Lincoln Beach, spent his own money to clear a path through the woods and brush, jumpstarting the restoration.

They also sought to shame the city into action, and after three years of lobbying, the city released a $24.6-million Request for Proposals to reopen Lincoln Beach. Subsequently, Congressman Troy Carter secured $1,500,000 for the Lincoln Beach redevelopment project from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Lake Pontchartrain Basin Restoration Program and $4,116,279 for the Lincoln Bridge Access Project (to build a walking ramp over the railroad tracks) in the FY 2024 spending bills.

For more than a year, no further progress has occurred. As one council member put it, speaking privately to The Louisiana Weekly, “We have a whole host of consultants arguing what should be on the property, and no one actually willing just to let people use the beach in the meantime.”

In July 2024, Lincoln Beach was officially named a national historic site, and Mayor Cantrell announced it would reopen in the summer of 2025. However, on Labor Day, the gates still remained locked, and any hopes for their unbolting have been pushed forward for another year. Undaunted, the beachgoers still jump the fence, and Latin music still flows from the sandy shores.

It is important to note that several attempts to were made to the Mayor’s office for comments about the project and the continued closure but had not received any response prior to going to press.

This article originally published in the September 15, 2025 print edition of The Louisiana Weekly newspaper.